A Study on Where the Tripitaka Koreana Woodblocks

May Have Been Carved

Park Sang-jin

(Emeritus, Kyungpook National University)

The Tripitaka Koreana printing woodblocks have harbored many secrets since the mid-13th century when they were engraved. This is primarily due to a lack of records indicating where they were carved, in spite of their enormous volume of 81,258 printing blocks. Fortunately, the woodblocks are well preserved, so scientific analysis should render some significant information to supplement the lack of records. The writer of this article is going to introduce new findings based on analyses of the woodblocks.

1. Profile of the Tripitaka Koreana Printing Woodblocks

A total of approximately 52 million characters are carved in the Tripitaka Koreana. Chinese characters are carved on both sides with each woodblock having about 640 characters. Besides the engraved portion, each woodblock has an end-piece (maguri) on both ends for ease of handling when making prints and when storing them. In most cases, the length of a printing block is either 78cm or 68cm, but some have lengths of 75cm, 73cm, or 70cm. They are 24cm wide, and the average thickness is roughly 2.8cm. Each block is about 1.5 times the size of a computer keyboard, and each weighs around 3.4kg. The total weight of all the blocks is approximately 280 tons, or, 70 truck-loads if loaded on 4-ton trucks. The total volume is about 450m3.

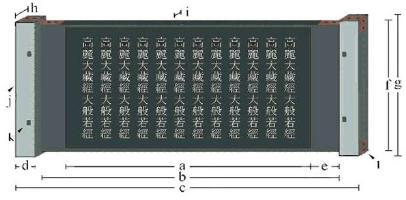

a: Length of the carving area where the characters are engraved (51cm)

b: Length of the printing block excluding the end-piece (64-74cm)

c: Length of the printing block including the end-piece (68-78cm)

d: Width of the end-piece (4cm)

e: Margin around the printing block

f: Width of the printing block (24cm)

g: Length of the end-piece (24cm)

h: Thickness of the end-piece (4cm)

i: Thickness of the printing block (2.8cm)

j: End-piece

k: Wooden peg used to fix the printing block and the end-piece

l: Pintle made of tin to link the printing block and the end-piece

2. Trees Used for the Printing Blocks

It was widely believed until recently that the Tripitaka Koreana woodblocks were made of birch(Japanese white birch). But birch wood was not found in the microscopic analysis made on about 200 samples of the printing blocks that the author collected in extremely small amounts. In the old days, sargent cherry trees and birch trees were described with the same Chinese character of '樺', so it appears that wild cherry trees were mistakenly identified as birches. The majority of the printing blocks were made of sargent cherry tree wood, followed by sand pear, costata birch, giant dogwood, painted mono maple, thunbergii camphor, and david popular.

|

Species of Tree |

QTY

(blocks) |

Ratio (%) |

|

sargent cherry, (Prunus sargentii) |

135 |

64 |

|

sand pear,

(Pyrus pyrifolia) |

32 |

15 |

|

costata birch,

(Betula costata) |

18 |

9 |

|

giant dogwood, (Cornus controversa) |

12 |

6 |

|

painted mono maple, (Acer mono) |

6 |

3 |

|

thunbergii camphor, (Machilus thunbergii) |

5 |

2 |

|

david popular, (Populus davidiana) |

1 |

1 |

|

total |

209 |

100 |

Sargent Cherry Trees

About two-thirds of the Tripitaka Koreana printing blocks were made from sargent cherry tree wood. They grow everywhere throughout the country, and its specific gravity of 0.6 makes it ideal for engraving, not too hard nor too soft. The other reason that sargent cherry trees were mostly used is because they are easy to identify by their dark reddish-brown horizontal lenticels, though some are short and others are somewhat longer. They could be recognized from afar, and could be singled out to be cut one at a time surreptitiously in the then Mongolian occupied countryside. In addition, in early spring they are fully covered with pink blossoms and easily spotted from a distance, which was yet another reason they were selected.

Sand Pear

The sand pear, used second most often in about 14% of the total volume of woodblocks, is a kind of wild pear. Found throughout Korea, it grows to be about 10 meters high. Compared to sargent cherry trees, the sand pear tree is more difficult to find, and its trunk is thinner, which is probably why it was not as widely used as the sargent cherry trees.

Costata Birch

The costata birch (Betula costata) belongs to the genus Betula, along with the Japanese white birch (Betula platyphylla var. japonica), erman birch (Betula ermani), schmidt's birch (Betula schmidtii), and dahurian birch (Betula davurica). Birches and costata birches have different leaves, though their bark looks similar. Birches usually have a white bark, whereas many costata birches have a yellowish bark. And that's why costata birches are identified in Chinese as 黃樺樹 or 黃檀木, meaning yellow-colored birch. They grow from as far south as the mountains of Jogye-san, Baegun-san, Jiri-san, and Gaya-san to as far north as the mountains of Sobaek-san, Duwi-bong Peak, Gariwang-san, Odae-san, and Seorak-san. Rarely do they grow at the foot of a mountain; they are alpine trees that grow usually at altitudes ranging from 600m to 1000m.

Costata birches grow to be about 30 meters tall, and their girth can be great enough that two adults can barely get their fully stretched arms around it. In the "gogu" season, literally meaning "spring rains for the crops", which comes in late April or early May, people will bore a hole in this tree's trunk to insert a tube and drink its sap. It is believed that the costata birch's sap in this season gives one long life. Our ancestors bestowed one more auspicious characteristic to costata birch trees, "geoje-su", by also calling "去災水", meaning "the water which eliminates disasters." And it has yet another Chinese name to cause confusion; when written as 巨濟樹, people think they grow on Geoje Island. But ribbed costata trees, geoje-su, have nothing to do with Geoje Island, though the two words sound similar. We will explore this in more depth.

* Tripitaka Koreana Printing Blocks and Birch Trees

Birch trees (Betula platyphylla var. japonica), or "樺木" in Chinese, are found to grow in the primeval forests of Baekdu-san Mountain, the high inland mountains of North Korea, the northeastern regions of China, Sakhalin Island, and Siberia. Birches are a cold weather species. Still, it is widely believed that the Tripitaka Koreana printing woodblocks are made of birch wood. All Korean textbooks teach that, and virtually all literature related to the Tripitaka Koreana adheres to the same "birch wood" theory.

If birch had been used to make the printing blocks, the trees would have had to have been logged on the high inland mountains of North Korea. Then the logs would have to have been rafted down to Hwanghae Province via the Amnok-gang (Yalu River, in Chinese) or the Daedong-gang River before finally being brought to Ganghwa Island. As all Koreans know, the Mongol armies occupied the whole country, including the capital of Gaeseong, at the time the Tripitaka was being engraved. Therefore, the birch logs would have had to pass through Mongolian occupied territory, which would have been a near impossibility. Nor was there any reason for birch logs to be transported so far because wild cherry trees and wild pear trees were equally good for carving. So it should have been obvious that birch was not be used to make the printing blocks, and this has been confirmed by scientific analysis.

Then how did this belief come about?

Firstly, the Chinese names for the trees caused much confusion. The character '樺' as we know today means "birch." But in those days, the same character designated both birch trees and cherry trees. Our ancestors used the same name for both species, not bothering to distinguish them. That was because both species were commonly made into bows or containers which required a smooth surface, for the thin bark of both trees could be peeled off like strips of paper.

A second possible explanation could be that they also used the name "巨濟木," meaning "trees from Geoje Island," which then came to be confused with ribbed birch trees, geoje-su. It is quite possible that many good trees grew on Geoje Island, with its nice climate and topography. In the book "Haein-sa yujin palman daejanggyeongpan gaegan inyu" (海印寺留鎭八萬大藏經開刊因由, lit. "the original reason that Haein-sa's 80,000 Carved Goryeo Scriptures were made"), it says that a man named Lee Geo-in (李居仁) made the printing blocks from "巨濟木." But this book is more properly considered a legend, due to the discrepancy between the time of its writing and the time the printing blocks were carved. Anyway, in this book, 巨濟木 should be interpreted as trees from Geoje Island, not ribbed birches (also "geoje-su"). Both birch trees and ribbed birch trees have a thin peel able bark that resembles paper, and because it is quite difficult for ordinary people to distinguish the two species, both were referred to simply as '樺.'

Thunbergii camphor

The use of thunbergii camphor is an important consideration in the controversy over where the carving was actually done. Thunbergii camphor trees grow along the southern coastline, on the islands of Dado-hae (meaning archipelago, or "the sea with many islands"), and on Jeju Island. This evergreen tree grows to be very big and tall and is quite common there.

Giant dogwood, painted mono maple, and david popular were also used for carving the printing blocks of the Tripitaka Koreana.

3. Location of the Carving Based on Wood Analysis

There are three reliable records relevant to the Tripitaka Koreana printing blocks. Firstly, it is written in the History of Goryeo (Goryeosa 高麗史) that in the year 1251, the king "had the Tripitaka Koreana printing blocks be engraved again over 16 years after the first publication was burnt". Secondly, about 150 years later, the Annals of the Joseon Dynasty (Joseon wangjo sillok 朝鮮王朝實錄) states that from the 10th to the 12th of May 1398, the king "went out to the Han River to watch the Tripitaka Koreana printing blocks being carried from Seonwon-sa Temple on Ganghwa Island." But no mention is found as to where the printing blocks went. On January 9th of the following year, 1399, it was written that "the Tripitaka Koreana was printed in Haein-sa Temple." From these records, people concluded that the Tripitaka Koreana printing blocks were "engraved over a 16 year period on Ganghwa Island from 1236 to 1251, and were kept therein, before being relocated to Haein-sa Temple in 1398." This theory regarding where the engraving was done will be reexamined here based on an analysis of the wood used to make the printing blocks.

Firstly, the surfaces of the printing blocks are flawless: there is no trace of any wear and tear that would have been inevitable if they had been moved over 400km from Ganghwa Island to Haein-sa Temple via Seoul. No trace of abrasion is visible to the naked eye, and not even one stroke of any character was found to be chipped. The surface of the printing blocks, seen through a microscope, is far from being even, consisting of numerous tiny grooves. With the minute characters engraved on them, surely many traces of damaged tree cells would remain even if the printing blocks had only touched each other or were shaken even slightly. The fact that there are no flaws indicates that they were carved at a nearby place and stored right away. There is no other explanation.

Secondly, the use of ribbed birch wood is a significant clue as to where the carving was done. Costata birches are alpine trees growing mainly in the mountains at altitudes between 600m and 1000m. This makes it unlikely that people would have taken the trouble to log and transport them from the mountains because there were plenty of other trees that could be used. However, costata birches also grow in the vicinity of Haein-sa Temple. Therefore, the fact some costata birches were used for the Tripitaka Koreana printing blocks suggests that those trees were most likely cut near Haein-sa Temple.

Thirdly, the sargent cherry trees and wild pear trees that compose the majority of the wood used for the Tripitaka Koreana printing blocks, can grow anywhere in Korea. But it is thought that they were logged on the islands near the southern coastline and in Jeollanam-do Province. The reason for this is that trees like the thunbergii camphor that only grow in warm climates are also found there, and at that time, the major transportation means was by water. In addition, we must consider the fact that the southern coastline was the only safe area during the war with the Mongol armies. Geoje Island and Namhae Island are possible places the trees may have been logged. Trees could have been felled there and cut into crude woodblocks, then carried to wherever the engraving was to be done, presumably at Haein-sa Temple and/or its vicinity.

From the analysis done on the printing blocks, we cannot accept the prevalent theory that the printing blocks were carved on Ganghwa Island. It is much more feasible and plausible that Haein-sa Temple itself or its vicinity was the actual carving location. If a broader assumption can be made, we could also allow that the southern islands, including Geoje and Namhae Islands, may have been where they were carved.

4. Reexamining Anecdotal Information Related to the Printing Blocks

As no record is available on the production of the printing blocks, many stories have been handed down by word of mouth. Here we will examine some of the prevailing stories. It is said that charcoal was buried beneath the Panjeon, the repository of printing blocks. We selected and dug in seven spots, but no charcoal was found. Up till now, it was believed that charcoal was buried beneath the Panjeon to control the humidity and to prevent the printing blocks from being eaten by worms. We confirmed that even without charcoal, the storage building, built on a well-drained slope, can adequately control humidity through humidity exchange between the soil and air in the building.

Only a few of the printing blocks were found to be lacquered. There are many who believe that the printing blocks were well preserved for 760 years because they were varnished with lacquer. But not all of the printing blocks were lacquered, nor is there any preservation problem with the printing blocks because they are being kept in a dry and well ventilated place. The moisture content of the printing blocks is about 15%, which is a safe level to prevent wood-rotting fungus, with or without lacquer.

Another widely held belief is that the logs were soaked in sea water for three years before they were made into printing blocks. The wood may have indeed been placed in the sea for transport and kept there during the production process, but that wasn't an essential measure. What was essential, though, was to boil the blocks in salt water before carving them. This practice is confirmed in the literature of that time. Seo Yu-gu (徐有榘), the author of the farming encyclopedia titled Imwon gyeongjeji (林園經濟志, lit. "Economy of the Lives in Forest and Fields") mentions in the volume on "Yi’un-ji" (about scholastic tastes and hobbies) how to make wooden blocks and how to preserve them after making prints. He wrote, "Saw up logs to make wooden planks, then boil them in salty water and dry up. Then the planks won't contort and will be easy to carve on." This confirms the fact that our ancestors also boiled the wooden blocks in salty water. The moisture content of raw and newly-cut planks varies between the inside and the outside; the surface dries quicker than the inside which eventually causes the wood to crack or to bend. On the other hand, if the plank is boiled in salty water, the salt that remains on the surface absorbs moisture, preventing it from cracking or bending, though it may take longer to dry out. Boiling in salty water has other merits: it draws out the resin so that the moisture in the plank is evenly distributed, softening the wood's texture and making it easier to engrave.